The purpose of this chapter is to detail the contrasting identities of two football clubs in South Manchester. The two clubs in question are Manchester City and their Semi Professional non-league equivalent Maine Road F.C. Whilst Maine Road F.C have never moved away from its class routes; City has excluded a large section of their original working class fandom. The two particular clubs epitomise the declining working class identity with football and the problems that have arisen as a result. In keeping with the investigation hypothesis, the 1980s will be of a key focus within the comparison as both clubs experienced dramatic changes during this period.

Before detailing the comparative case study it is important first to detail a Manchester’s footballing history. The city has deep working class roots and so do its football clubs. Manchester City Historian Gary James best details the working class connection with the club. He details how ‘In 1900, 57% of the club’s shareholders in were owned by manual labourers, whether that be Skilled, Semi-Skilled of Unskilled. [1] Although a focus on the clubs’ shareholders may not provide concrete evidence as too class identifications, the results overwhelming suggest the working class sector of society had a strong relationship with the club. The data provides a stark difference to Manchester City’s current billionaire Sheikh Owners. James credits Manchester City’s F.A Cup win in 1904 as furthering the relationship as it established an ‘enduring football identity for the city’.[2] Manchester City had a mutually beneficial and strong relationship with its supporters. A club advertisement from 1933 was featured in The Northern Whig newspaper and offers supporters a match ticket and travel pass for 9 shillings and 6 pence, the equivalent of around 50p[3]. However, the relationship would deteriorate particular in the late 1980s and would result in wholescale alienation in the Premier League period.

Maine Road F.C have preserved their working class roots. A lack of commercial interest combined with affordable football means non-league football has become appealing to many priced out of the modern game. A working class demise is yet to take place at this level: ‘The soul of football is still there, you just have to look harder… it’s hidden in the lower leagues of England’. [4] Prior to Road’s match I spoke to Club Secretary Derek Barber who has been ever present at the club for the past thirty years. He told me that City supporters choose Maine Road because it’s affordable and they can no longer afford to watch regular Premier League football. My questionnaire results would back him up as over 80% agreed it was no longer viable (see Fig 1). The reasons behind Maine Road F.C’s appeal are both financial and personal. Maine Road’s ticket structure is more inclusive, £5 for a ticket and pie serves as a comforting reminder to football’s collective days. The programme from their fixture features adverts for local tradesman ranging from Plumbing, Cleaning and low level retail industries.[5] In many cases the businesses usually sponsor a player too. This low level commercialism is more familiar to Manchester’s working classes rather than the wealth bewildering adverts of Manchester City’s equivalent. Of course the financial barrier is the biggest obstacle. However, the practicality of watching Manchester City is also a hindrance. This season, City have played just four home games at the traditional kick off time of Saturday at 3 o’clock, this compared to Maine Road who have played fifteen.

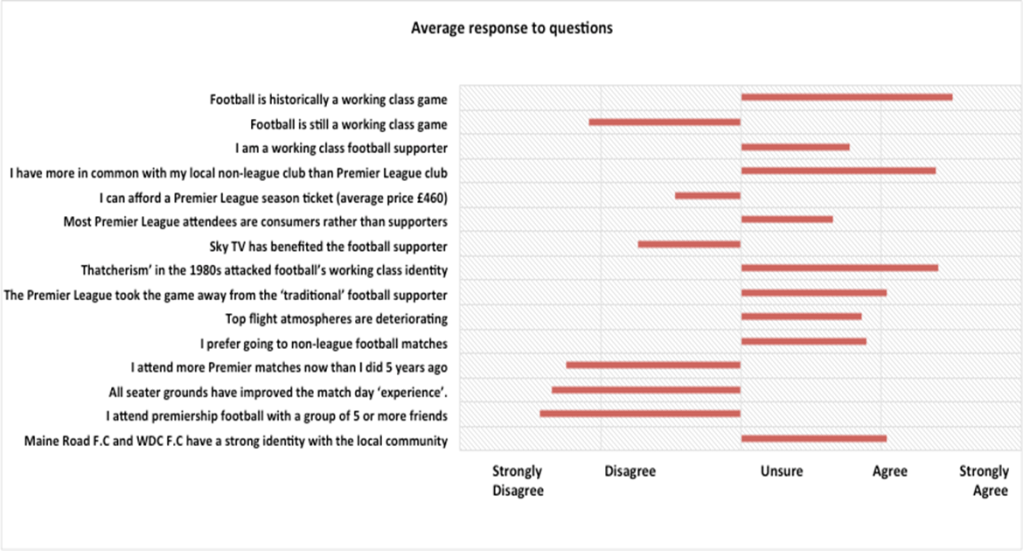

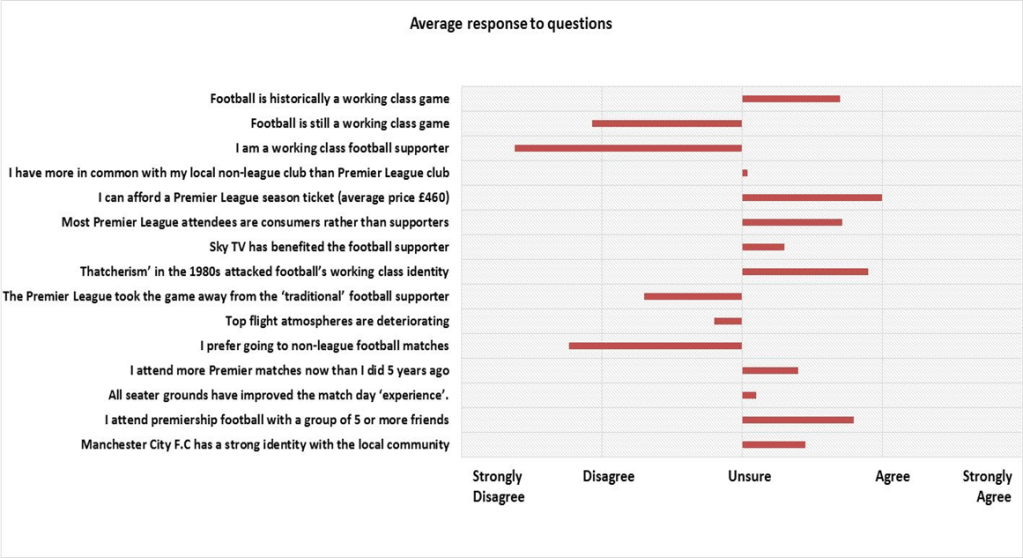

At both Manchester City F.C and Maine Road F.C I handed out questionnaires to both sets of supporters. The questions addressed the key areas of my study: Class consciousness, Thatcherism, commercialism, identity and the Premier League. The questionnaire uses a Likert scale in order to not force a viewpoint on the participants and make the data readily quantifiable. I used a numerical scoring system to interpret the level of agreement/disagreement between both sets of supporters. A score of +2 was awarded for supporters whom strongly agreed with the statement, +1 was given to those who just agreed whilst a score of 0 was allocated to those who were unsure. Similarly, a valuation of -2 was awarded to those who strongly disagreed with the statement and a score of -1 to those who disagreed.

I visited Maine Road F.C for their South Manchester Derby v West Didsbury and Chorlton on the 31st March 2017. The following week I travelled to the Etihad Stadium on the 8th April to see Man City take on Hull City. The results from my study are detailed below:

Fig 1, Average response to questions from 50 Maine Road F.C supporters. (For detailed analysis of the results please see appendix.)

Fig 2, Average response to questions from 50 Manchester City F.C supporters. (For detailed analysis of the results please see appendix.)

Both questionnaires paradoxically refute one another. Both supporters categorise themselves differently in terms of class and identity. At Maine Road’s fixture, a positive score of +0.78 classified themselves as working class whilst Manchester City supporters provided a score of -1.62. Therefore it was clear from the outset that both studies were likely to contradict one another. In terms of identity, 48 out of 50 non-league supporters felt they had more in common with their clubs rather than their Premier League club, this equating to a score of +1.39. As highlighted by figure 2, the overall consensus from Manchester City supporters provides no real opinion on the same matter. This result conforms to the trend of the Manchester City study which overall provides inconclusive responses. One possible explanation for the lack of opinion is down to a lack of knowledge about the history of City’s football fandom.

The contrasting affiliations can be explained geographically. Whilst Maine Road is situated amongst the houses and at the heart of West Didsbury’s community, City’s Etihad campus is located in an industrial wasteland of East Manchester. The strength of Maine Road’s identity was shown only two years ago when local supporters and businesses raised the £2,500 needed to keep the club running. In an interview with the Manchester Evening News following the success, Chairman Ron Meredith noted that ‘the club couldn’t run without the generous donations and sponsorship from City’s supporters and local businesses’.[6] The fundraising reinforces that what Maine Road lacks in spending power it more than makes up in fan power. Maine Road’s current sponsors are the Manchester City Supporters Trust, this demonstrating the strong connection between club and fans.

A similar identity is now non-existent at Manchester City. The real crisis of identity for Manchester City supporters occurred during their move from Maine Road to the City of Manchester Stadium (now Etihad Stadium), in 2003. For the majority of supporters, a specific fan culture and distinctive atmosphere was synonymous with Maine Road. Maine Road provided a sense of belonging and the relocation was deeply disorienting to most City fans and was accompanied by a powerful sense of loss.[7] The identity was shared by the players too. Captain Shaun Goater stated prior to the last ever match in Maine Road in 2003: ‘it may not be the prettiest place to play football, but you can feel the history everywhere and the atmosphere is always tremendous’.[8]

The move eastward to one of Manchester’s most deprived areas would mean supporters would no longer arrive to the ground in a comparable manner. At Maine Road, a ‘number of pubs, shops, cafes and mobile traders lined the streets and served as points of animation, as fans stopped, chatted, drank and ate with friends and fellow supporters’.[9] Due to the industrial poverty of Eastlands, this was no longer possible. The surrounding areas of the Etihad Stadium are amongst England’s poorest: 45.6% of Manchester’s neighbourhoods are in the most deprived in the country, of the 19 areas, the top seven are all former working-class neighbourhoods in the east, around the Etihad Stadium’.[10]

65% of Manchester City supporters accepted that the majority of current Premier League attendees are consumers rather than supporters. Manchester City’s recent financial and global experiments highlight the shift. Manchester City match-goers now arrive from all over the world. A look at the club’s official website shows that City boasts 14 International Supporters Clubs worldwide. The majority of supporters now bypass the local community and meet within the grounds of the Etihad. Manchester City’s annual report from last season detailed that the club achieved revenue of £391.8 million[11], with match day revenue boasting the biggest improvement in the Premier League. Match-goers now congregate around ‘City Square’ a fan zone created by the club which features food, drink and live music whilst the club shop is busy selling City merchandise. Hospitality doors open well in advance to kick off and prices start at £500 and rise to £25,000 per match. The latter exceeding the average annual yearly wage for every region of Greater Manchester. A supporter whom engages in this pre match practise is likely to be referred to by a more ardent supporter as a ‘day-tripper’. Whilst a supporter is likely to be active and vocal during a match, a consumer of the sport is a passive bystander to the unfolding events. As a result, the modern football consumer has become a burden for the traditional working class supporter. Remaining city fans in this category are often filled with nostalgia for how football and their football club used to be. A relevant terrace chant which is still sung at the Etihad today is as follows:

We are not, we’re not really here,

We are not, we’re not really here,

Just like the fans of the Invisible

Man, We’re not really here

There is some dispute as to the circumstances of the chant’s origination. The club’s official website concludes that the song “pays homage to the fans that continued to follow City when they were in the old third division”[12]. The chant pays tribute to those supporters who were their when City weren’t the European billionaire giants of today. An argument can also be made that the chant takes a swipe at the new wave of consumers arriving at the Etihad to celebrate City’s new founded success.

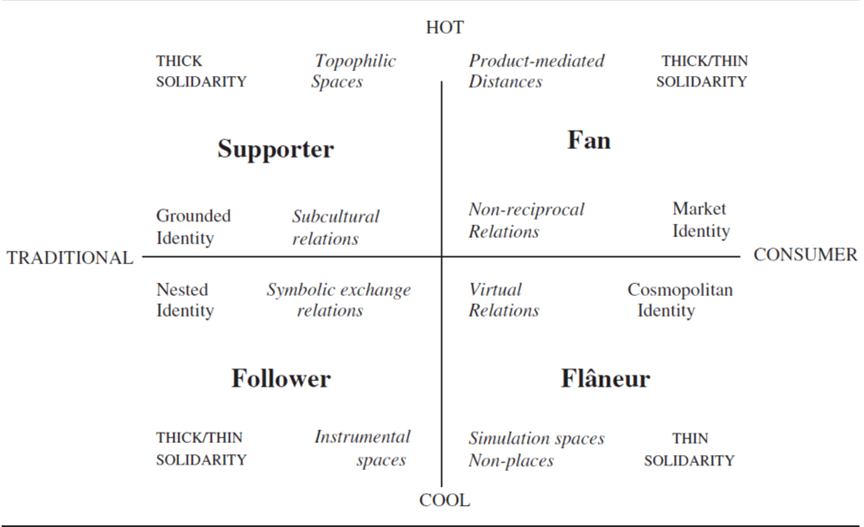

For the purpose of this paper, it is important to study and emphasise Manchester’s footballing identification shift in the 1980s. Richard Guilianotti’s identification model pinpoints the 1980s as football’s key period of ‘hyper commodification’. He argues that at this point ‘sports identification moved away from the supporter’s model and towards a consumer-orientated identification of the flaneur’.[13] Specifically, Guilianotti’s quadrant analysis of Identifications (Fig 3) addresses Supporters, Fans, Followers and Flaneur. The identifications displayed below are contrastingly applicable to both Maine Road and Manchester City F.C supporters.

Figure 3. (R Giulianotti, R. (2002).

The traditional/consumer horizontal axis marks a shift in identifications.

Applying this the case study, it is clear Maine Road supporters would lie firmly on the left hand side of the quadrant as fans here share a grounded identity and local cultural identification.[14] This compared to Manchester City’s new brand of supporter who holds a market identity a central focus on consumerism. My questionnaire results also reinforce Giulianotti’s conclusion as all but two participants at Brantingham Road agreed they had more in common with their local non-league club as opposed to their local Premier League club.

Furthermore the vertical axis is labelled hot and cold and reflects the ‘different degrees to which the club is central to the individual’s project of self-formation’. [15] The majority of Manchester City supporters are situated on the cooler side of the model as they lack any real power and influence with their club’s operations. However for a lot of people at Maine Road, the club is a part of who they are. From the lady who runs the tea bar, to the man on the turnstile, the club helps those individuals rise to importance within the surrounding community. A big reason for attendance is down to the collective strong relationships built at the football club.

My study also re-affirms the 1980s as the pivotal turning point. Of the Maine Road F.C supporters aged 40+, twenty out of twenty two participants agreed that the Thatcher administration negatively impacted upon football’s working classes (see Fig 2). Interestingly, one supporter in the comments section of the survey noted ‘I lost my job at the Sharp factory in 1984 and could no longer afford to go to City’ (see appendix). The supporter wasn’t alone, as Thatcher’s attack on manufacturing industries would result in an unemployment rate of 15.4% in Greater Manchester by July 1985.[16] The result meant Manchester’s working classes could no longer afford to go to football matches. Manchester City attendances declined from an average of 35,272 in 1980 to 19,442 in 1988.[17] Whilst Manchester City was struggling in the 1980s, Maine Road was expanding. Non-league football is often seen as a new development however the 1980s marked Road’s most successful decade. Road finally had their own stadium at Brantingham Road in 1980 and went on to win four back to back league titles from 1982 to 1986. The success on the pitch was as a result of Manchester City’s misfortunes. A number of key figures including current Chairman Ron Meredith and club secretary Derek Barber had themselves been priced out of City and turned their attention to the project at Maine Road.

The 1989 Hillsborough disaster and subsequent Taylor Report changed Manchester City’s iconic Kippax’s 18,000 strong terrace to all-seater in October 1995. City supporters still nostalgically reminisce of the powerful atmosphere generated by the stand: ‘Fans remember the atmosphere to which this contributed and like fans of other clubs, they point to the dearth of such an atmosphere in modern stadia’. [18] During the Kippax’s standing existence, tickets were very cheap, in the 70s supporters could get a season ticket for £11. However, ticket prices rocketed from the outset of the report as a result, many of the idiosyncrasies and quirks of stadiums have been removed’.[19] Often nicknamed the ‘Emptyad’ by rival fans, Manchester City’s Etihad Stadium is often mocked for its lack of atmosphere. An article from the Daily Mail in 2016 highlights just how ticket prices have risen. The passage shows City fans protesting at the price of £62 tickets for their fixture against Arsenal at the Emirates Stadium. A spokesman for the Manchester City supporters group City Watch is quoted as saying ‘Turn your back on the fans and we will turn our backs on you’.[20] Gary James is a key Manchester Football Historian, the data below is specific to Manchester and serves to emphasise football’s unattainability to Manchester’s working classes. Initially Manchester blue collar workers could attend matches with spare change they had accumulated from just a few hours week. However, rocketing ticket prices mean match choices need to be carefully considered by this section of society. James highlights how supporters from the factory, engineering, and bricklaying industries could purchase a Manchester City ticket for around 2-3% of their average weekly wage. [21] James compares this a century later to highlight football’s disproportion in comparison to the average minimum weekly wage. In 2013, the cheapest ticket Manchester City ticket equates to 14.8% of a weekly wage and the most expensive stands at 33%.[22] Since James’ study the disparity has only accelerated.

Finally, it is important to anticipate the future for both clubs and their contrasting fandoms. It’s understandable why Manchester City’s Sheikh Owners won’t want to change their business model any time soon. The club, like all Premier League clubs aims to make the most revenue. Therefore affordable pies for fans are unsurprisingly chomped by more lucrative hospitality packages. Other than a respect of tradition, there is no real incentive for clubs to change their stance. The consumer is distinctly more valuable to Premier League clubs than that of the traditional supporter. With the situation as it is in now, the future is bleak for working class fandoms across England.

On the other hand, the future for Non-League clubs like Maine Road remains more uncertain. As noted by the Vice Chairman Colin Broadbent in his programme notes: ‘Maintaining a football club at this level has become increasingly costly. The club has always had a number of core friends who have supported it by means of donations, sponsorship, advertisements and by attending the games… the brutal truth is that this is no longer enough and new initiatives are required’.[23] The club will become increasingly vulnerable and as City economically progress it is unlikely the same can be said for Maine Road. On the other hand, linking back to the questionnaire, Road fans gave a positive score of +0.88 in favour of non-league football over Premier League football. The valuation is a surprising response as obviously on a football level the standard and quality is at a vastly superior level. However, supporters don’t just prefer non-league football for the ninety minutes; rather the collective experience provides a nostalgic reminder for supporters. It is important to note this comparative case study is a mere microcosm to football’s current situation. Maine Road rivals F.C United were formed in 2005 to contest Manchester United’s ownership under the Glazer regime. A.F.C Liverpool was set up in 2008 by a group of over a thousand fans who had been priced out of their season tickets at Anfield. Therefore the response and current evidence perhaps offers a level of optimism for the future of working class involvement in football. However, with average attendances not surpassing the 200 mark in the North West Counties division it is clear most fans have been priced out of football altogether.

[1] James, Gary. 2014. “FA Cup Success, Football Infrastructure And The Establishment Of Manchester’S Footballing Identity”. Soccer & Society 16 (15): 201-217.

[2] James, Gary. 2014. FA Cup Success… Establishment Of Manchester’s Footballing Identity”, p 212.

[3] Northern Whig Newspaper. 1933. “Cheap Day Excursion Tickets”.

[4] Tassell, Nigel. 2016. The Bottom Corner: A Season With The Dreamers Of Non-League Football. 1st ed. London: Yellow Jersey Press.

[5] “Match Preview: Maine Road F.C V West Didsbury & Chorlton F.C”. 2017. Maine Road F.C.

[6] Collins, Ben. 2015. “Maine Road FC Bridge 60-Year Gap With Manchester City Supporters Club Deal”. Manchester Evening News.

[7] Edensor, Tim. 2014. “Producing Atmospheres At The Match: Fan Cultures, Commercialisation And Mood Management In English Football”. Emotion Space And Society 15 15: 82-89.

[8] Daily Mirror. 2003. Saturday May 10th. “MAINE EVENT”.

[9] Edensor, Tim. “Producing Atmospheres At The Match…”

[10] Conn, David. 2014. Richer Than God: Manchester City, Modern Football and Growing Up. 1st ed. New York: Quercus.

[11] Manchester City. 2017. OURCITY. Manchester City Annual Report 2015-16, p 3.

[12] “- Manchester City FC”. 2017. https://www.mancity.com/news/club-news/club-news.

[13] GIULIANOTTI, R., 2002. Supporters, followers, fans and aneurs:

a taxonomy of spectator identities in football. Journal of Sport and Social

Issues, 26 (1), pp. 25-46.

[14] GIULIANOTTI, R., 2002.

[15] GIULIANOTTI, R., 2002.

[16] Unemployment Rate in Manchester. 2016. Office of National Statistics. London: Freedom of Information.

[17] Attendance Data. European Football Statistics. http://european-football-statistics.co.uk/

[18] Edensor, Tim. “Producing Atmospheres At The Match…”

[19] Mainwaring, Ed, and Tom Clark. 2011. “‘We’re Shit and We Know We Are’: Identity, Place And Ontological Security In Lower League Football In England”. Soccer & Society 13 (1): 112..

[20] Gaughan, Jack. 2016. “Manchester City Fans Voice Disgust At Ticket Prices For Champions League Clash With PSG”. Daily Mail.

[21] James, Gary. 2014, p 210.

[22] James, Gary. 2014, p 210.

[23] “Match Preview: Maine Road F.C V West Didsbury & Chorlton F.C”. 2017. Maine Road F.C.